Chaper 4: Silents in Sound

1. With the advent of sound-on-film technology, many cinema musicians found their positions rendered obsolete. Although pressure from musicians and the cinema music industry persuaded some theater managers into keeping in-house musicians through the end of 1929, it wasn’t enough to overcome the excitement created by the new technology, and the films that used it. A handful of accompanists found themselves both playing the organ or piano and the phonograph: Adele V. Sullivan’s collection of cinema music includes cue sheets for records to be synchronized with scenes. A number of cinema musicians found new employment in radio, where Rosa Rio, for example, became an even more famous accompanist and composer, creating the theme for Orson Welles’s The Shadow and other radio plays. Others sought out church jobs, teaching, or playing for live stage entertainment. Still others decided to go into different fields entirely—Hazel Burnett became a dentist—and some, unable to find work, committed suicide. (American Organist 12, no. 7 (1929), 489)

2. At the same time, the film industry on the East Coast was changing rapidly. Filmmakers had moved west to avoid copyright and other legal issues that were pursued more stringently in the east, and to take advantage of the weather, which permitted outdoor shooting all year round. It might seem natural that cinema musicians, especially composers and arrangers, would seek out work in Hollywood writing the scores for sound films. While this was true for a handful of composers and film music arrangers like James C. Bradford, Edward Kilenyi, Hugo Riesenfeld and J. S. Zamecnik, whose pieces and recommendations for scoring silent films were turned into scores for sound versions of those films or “part-talkie” films such as the 1928 Al Jolson vehicle The Singing Fool, most of the composers for new sound films were from non-cinematic backgrounds. Max Steiner, who scored King Kong, was born into a theatrical family in Austria and wrote classical music before joining his father and colleagues in the theater, where he composed operettas or incidental music for plays. After working in Berlin and London, Steiner went to New York where he worked on Broadway until 1929. There he came to the attention of producers of both stage plays and films, including vaudefilm-turned-movie company RKO, which hired him to create scores for its shows. Moving to Hollywood, he soon became in high demand for original or arranged film scores. Steiner’s biography is echoed in those of the other major early sound composers, including composers Bernard Herrmann, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman, Miklós Rózsa, Dimitri Tiomkin, and Franz Waxman. Korngold was a celebrated art music composer of ballets and opera in Austria before leaving during the Nazi rise to power in the 1930s and at the invitation of Max Reinhardt to come to Hollywood to score Reinhardt’s film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Waxman went from conducting a band to studying with conductor Bruno Walter to becoming an orchestrator in the German film business before immigrating to the United States.

3. It’s unclear why established cinema composers, arrangers, and performers weren’t wooed en masse by Hollywood when sound film was in development, or why they weren’t used to score more part-talkie films. Perhaps, as had happened in the cinema industry at its birth, when it struggled to establish film as a wholesome and employed credentialed stage actors in order to show that it was a moral art form, Hollywood studios sought out those with authority as art music composers to help establish the new sound film as an art. Those who had pushed back against sound film, decrying it as “canned music” without emotion and without the capability to truly express the emotions or actions of the visuals, likely wouldn’t have been hired because of their attitudes, but there were countless silent cinema composers and compilers who would have been enthusiastic about the chance to create permanent scores for films. (“Canned Music on Trial,” 1929) Nevertheless, the composers who found work in Hollywood at the beginning of the sound era were familiar with the sounds and music of the silent cinema, how that repertoire was selected and performed, and what it signified for audiences. This was true for spirit films as much as it was for westerns, romances, and other genres. Additionally, séances as a form of entertainment remained popular through the 1930s, and the sounds of the séance continued to be part of widespread general knowledge. The losses from the Great War were still in recent memory, and Spiritualist leaders remained active, seeking to resolve the conflicts between their religion and Christianity and establish more permanent centers for Spiritualist study and practice. As Jenny Hazelgrove has documented, the egalitarian nature of Spiritualist beliefs was appealing to many, and interwar belief was high:

Spiritualism was every bit as popular interwar period as it had been in the previous century. Spiritualism reflected the increasingly democratic values of the twentieth century. the movement continued to grow. Indeed, the interwar turned out to be a boom time: Heterodox Christianity and widespread belief in the supernatural simultaneously supplied a rich resource Spiritualistic thought and a cultural setting where conversion to could feel natural and even inevitable. Spiritualism’s preoccupation the miraculous linked it to popular Catholicism, as did its view afterlife and relations to the dead. (Hazelgrove 2000, 2)

Hazelgrove goes on to note the comfort provided by spirit films that offered a glimpse of life beyond death:

A competition organized by the Sunday Dispatch in 1940 revealed that many people dreamed of postmortem survival and of reunion with dead loved ones. The newspaper offered to award a prize for what ‘readers considered the best film fade-out they had ever seen.’ Mass-Observation [a group dedicated to studying everyday life] analysts handled the findings and were struck by ‘the emphasis on supernatural endings…: 20 per cent of the votes cast were for fade-outs with the spirits of the dead living happily in the other world although they could not do so in this.’ The most popular fade-out was The Three Comrades (1938), where two dead comrades beckon the third to join them. Smilin’ Through (1932), which dealt with the theme of communication between the dead and the living, was also popular. (Hazelgrove 2000, 25)

Hazelgrove further documents that there was also a strong school of thought that even those who had not lived unimpeachable lives had the opportunity to improve their afterlives and move up from lower levels of the afterlife to higher, more privileged ones. This idea is an old one, rooted in Catholic belief in Purgatory: in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the ghost of Old Hamlet tells his son that he is

Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night,

And for the day confined to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. (1.5.10-13) (Shakespeare 2006)

4. It is not surprising, then, to find examples of this belief expressed in the spirit films of the 1930s. A 1935 cinematic adaptation of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol titled Scrooge emphasizes Marley’s ghost’s lines in which he states that he must wander the Earth, carrying great chains, to expurgate his sins. This idea also drives The Ghost Goes West from the following year; in it, a disgraced ghost must restore honor to the family name before he can go to heaven. And in the 1937 film Topper, happy-go-lucky but utterly irresponsible couple George and Marion Kerby (Cary Grant and Constance Bennett) must perform a good deed as ghosts in order to be fully released from life on Earth. It is unsurprising that all three of these films have scores that tap into the sounds of the séance and the ways in which silent spirit films were accompanied.

Ghosts from the 1930s

5. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, first published in 1843, was a popular source for filmmakers. It was used as the basis for one of the first feature silent films in 1901, and also served as the basis for one of the earliest surviving sound films involving spirits. There is little contemporary documentation regarding the music used for any of the silent or early sound versions of A Christmas Carol, possibly because it was thought to be too obvious to need recommendations or cue sheets. It’s likely, though, that accompanists employed traditional Christmas music along with stingers or other gestures or timbres suggesting the supernatural when Marley’s ghost and the other spirits appeared. In 1911, Edison’s British Amberol division released a recording of Bransby Williams’s piece “Awakening of Scrooge,” which includes a performance of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen” and some spoken text from the Dickens story; and “Street Watchman’s Christmas” by Williams and Charles J. Winter, both likely intended to be used to accompany films, magic lantern shows, or readings of Dickens’s novella. (Edison Phonography Monthly 1911, 19) Reviews and synopses—such as the one for a 1917 film version of A Christmas Carol directed by Rupert Julian—note the role of carolers in setting the scene of the film, describing “the merry voices of young and old picking up Christmas cheer and passing glad tidings in friendly salutations.” (Moving Picture World 1917) A brief review in Exhibitors Herald of a 1924 adaptation states that for a Chicago screening of Scrooge, a two-reel Art Class film, well-known Tiffin Theater organist W. Remington Welch “played ‘Christmas In the Old Neighborhood’ on the Wurlitzer organ.” (Exhibitors Herald 1924, 35)

6. Directed by Henry Edwards and filmed in the United Kingdom, the 1935 Scrooge has an original score by Dutch composer William (W. L.) Trytel. Unlike many of the film composers in sound film in Hollywood, who had not worked extensively in silent film, Trytel had served as the composer and music arranger for several silent films before becoming the music director for sound films at Twickenham Studios in London. Trytel clearly knew the musical expectations that the various earlier films and countless stage adaptations of A Christmas Carol had created for audiences, including carols and appropriate music for spirits. In addition to various Christmas songs, performed with deliberate woefulness by amateur players and sung by children, Trytel’s score makes use of several silent film music genres, including a misterioso, as heard at 13:15 in the film, and a hurry, which begins at 13:36.

7. More relevant to Scrooge’s status as a spirit film, however, is the music Trytel composed or repurposed for the appearances of Marley’s ghost and the other spirits. A stinger and a shimmering cymbal, both sonic signifiers borrowed directly from silent film, accompany the traditional shot of Marley’s face in Scrooge’s doorknocker that first suggests the presence of the otherworldly in the story. Tremolos and chromaticism reflect Scrooge’s fear and anxiety as he enters his home following this fright (starting at 19:19), and when he sees his own clothes (20:46) and mistakes them for a human figure, Trytel scores the moment with another stinger followed by more tremolos. At 20:28, a bell begins to ring by itself, a common signifier of spirits in séances that also found its way into the silent cinema. Remarkably, Marley’s ghost is unseen throughout the film, but the continuation of tremolo in the strings beneath his dialogue clearly indicates his presence using a traditional musical texture for spirits. Marley’s ghost’s music establishes the basic musical soundscape for the rest of the spirits in the film. Trytel uses typical gestures from the misterioso genre, already associated with spirits in the audiences’ ears, to emphasize Scrooge’s fears in anticipating the spirits to come. The Spirit of Christmas Past, portrayed as a human figure with a glowing aura, appears to the accompaniment of stingers and the same shimmering cymbal that indicated Marley’s ghost’s arrival.

8. The arrival of the Spirit of Christmas Present is announced through chromatic glissandos in the strings and the harp, creating a sense of eeriness. This established music for spirits is disrupted, however, when the spirit turns out to be a cross between Santa Claus and Bacchus, wearing fur-trimmed robes and a crown of vines. The eerie spirit music is replaced by a jolly march featuring the brass, confounding the audience’s expectations for a more ethereal figure. After this unorthodox spirit of Christmas Present has come and gone, Scrooge must face yet one more spirit: that of Christmas Future, who shows Scrooge his own death. When Scrooge awakens for this final visitor of the night at 39:21, Trytel scores the scene with low winds briefly oscillating to suggest instability or the unnatural and the same cymbal roll as that of Marley’s ghost’s arrival. A looming, pointing shadow, the Spirit of Christmas Future is then accompanied by a funeral march that begins at 39:37 (Fig. 4.1). Trytel then transforms the march in various ways, again upending expectations, by making it triumphal in nature and shifting it to a major key as the Spirit of Christmas Future departs and Scrooge awakens, changed, to church bells ringing on Christmas morning.

Figure 4.1 Scrooge’s funeral motif

9. Throughout, Trytel’s score has brought the sounds and music of séances and silent spirit films to the sound picture, anticipating audience expectations and creating a new accompaniment filled with the established musical tropes, textures, and techniques for spirits. Hailed as “decidedly effective,” Trytel’s score, which openly incorporated musical gestures and textures associated with spirits from the silent era, clearly communicated the presence of spirits without seeming either old-fashioned or too far removed from the accompanimental practices of the silent film. (David 1935, 15) That there was such close continuity in scoring for spirits from the silent cinema to sound films demonstrates that the sonic concept for the benevolent or warning spirit remained unchanged even as newer musical and sonic tropes developed for other genres within sound film. Scrooge was an enormously successful spirit film of the early sound era, and the positive reception of Trytel’s music for the spirits enabled other composers to continue to use similar musical approaches drawn from the silent era for spirits critically unchallenged.

10. In The Ghost Goes West, a 1936 satire about American materialism, phantom Murdoch Glourie (played by Robert Donat), who died “a coward’s death” in the 18th century, is attached to his family castle and cannot be admitted to heaven until he convinces a member of the McClaggans family—a rival clan—to admit that “one Glourie can thrash fifty McClaggans.” When Glourie’s ancestral castle is sold to an American, dismantled, shipped across the Atlantic, and rebuilt in Florida, Glourie’s ghost goes with it.

11. The score for the film is by Michael Spoliansky, who grew up in a family of professional classical musicians and composed for cabarets in Berlin before fleeing to London when Hitler came to power. Once in the United Kingdom, he began scoring films for British filmmakers, eventually composing numerous scores for directors including Otto Preminger and Alfred Hitchcock. Like Trytel, Spoliansky uses conventions from silent film accompaniment for the spirits in The Ghost Goes West, reifying the persistence and familiarity of these techniques in the early sound period. His score also, again like Trytel’s, includes other generic music clearly derived from silent film accompaniment like hurries, mysteriosos, and music for comedic scenes. The influence of silent film accompaniment techniques is also obvious in Spoliansky’s use of highly mimetic music, a common device in which the music parallels the actions of the actors. (For more on mimesis in silent film, see Leonard 2018)

12. The Ghost Goes West opens with a prologue that illustrates just how Murdoch Glourie became a ghost by hiding from his rivals behind a barrel of gunpowder, which is then shot and explodes. This prologue is accompanied by and orchestral score that establishes the setting as Scottish through the use of bagpipes, drums, and gestures from traditional Scottish music. After the barrel explodes (11:26), the music shifts from the bagpipes to a modern flute, which plays a long line that mimics the actions of the surrounding men as they watch Glourie’s cap rise high into the air and fall again. While the flute’s ascending line is a straightforward scale, it trills at the top of the ascending line, as if trying but unable to rise any higher, and its descending line is chromatic and full of sequences that emphasize its downward movement, indicating that Glourie hasn’t risen to heaven, but is remaining on earth as a spirit. In the following shots, which show spinning circles surrounded by clouds and are accompanied by static strings, Glourie’s father tells him that they are in limbo, and cannot move on until Glourie’s ghost has avenged the family honor, smudged through his “cowardly” means of dying. Although bells and trumpets follow, they herald only the return of Glourie’s tam—all of him that remains—to the castle, rather than signifying his spirit’s arrival in heaven. After his tam is laid in state, Glourie’s ghost appears for the first time, to the sound of shimmering cymbals—the same instrument and technique used to betoken the ghost of Jacob Marley on film in Scrooge just a few months earlier. As Glourie begins his nightly walks through the castle, the score provides signifiers of the spirit straight from the séance and the silent cinema: bells ring and the clarinet has a wandering, unsettled, chromatic melody.

13. Once the film has jumped to the modern setting, the ghost’s nightly arrival begins with the clock striking twelve (33:08), a glass shattering, a descending line in the piano and then orchestra, (33:28), and rapping. The camera then cuts to Peggy Martin (played by Jean Parker), the daughter of the rich American who will buy the castle and take it and its ghost to America, who hears the sounds of the ghost walking about the castle. The music changes: the upper winds have a melody accompanied by tremolo violins and a strumming harp. So while the initial scoring suggests that the Glourie ghost’s reputation is frightening, the shift to music indicative of heaven tells the audience that he is not. Indeed, his appearance is so innocuous that Peggy mistakes him for his living descendent, Donald Glourie (also played by Robert Donat). Spoliansky’s use of these established sounds of the séance and of the afterlife from silent film accompaniments demonstrate the ubiquity of these signifiers for the supernatural, and for the benign spirit in particular. The castle staff admit to never having stayed late enough at night to have actually encountered the ghost, and once Peggy has met the spirit, it’s clear that the ominous scoring at the beginning of the scene reflects their fear of the ghost rather than the ghost’s actual appearance or purpose.

14. While the castle’s parts are being transported by ship to the United States, Murdoch Glourie’s ghost rises from the neatly wrapped packages of stone to the accompaniment of flute trills, plucked strings, harp, and celesta, affirming his non-threatening status (44:36). The following scene, which depicts Murdoch’s nightly walking and rapping, is scored with low pitches on the piano, low brass, and repeated short crescendos. This more traditionally mysterious music again suggests that Murdoch the apparition could potentially be frightening to those who associate spirit rapping with malevolent phantoms, but Murdoch’s behavior—which is habitually flirtatious—is far from mysterious. He spends most of his time either playing a kissing game with young women or explaining how he is tied to the castle until he can lift the curse.

15. After the castle has been rebuilt, the Martins hold a grand dinner at which they promise Murdoch’s ghost will appear, secretly dressing Donald Glourie as his ancestor in cases the spirit is a no-show. And while Murdoch initially resists making an appearance, he finally does so after a guest, Bigelow, proclaims that he is the last living McClaggan. Murdoch’s entrance (1:14:23) is signified by whistling, the sound of wind, and chromatic, metrically irregular tremolos in the strings, suggesting that Murdoch will be rather more sinister now that his chance to get to heaven as arrived. But this typical ghost-music soon becomes comedic, as Murdoch chases Bigelow around the castle, popping up right in front of Bigelow at every turn. The mimetic quality of the chase music, while not linked to the sounds of the séance or more mournful spirits, is directly from the silent cinema: using the upper winds and quick motifs, Spoliansky creates an antic atmosphere that culminates in a line that descends through the ranges of the winds as Bigelow falls down in front of Murdoch (1:15:19).

16. Music indicating Murdoch’s scarier side comes into play again, however, as he tries to make Bigelow swear that Glouries are better than McClaggans (1:15:28). Crescendos rise to shrieking figures that prefigure the score for Psycho (1960), and drums thunder beneath tremolos and trilling winds. Although Murdoch’s appearance doesn’t change—he’s still full-bodied and gore-free—he is clearly terrifying to Bigelow. Murdoch pulls Bigelow out of the castle through the walls and into the open sky to force Bigelow’s concession about the value of MacClaggans relative to Glouries. A descending chromatic line in the flutes mimics Bigelow’s return to the castle, where Murdoch has vanished. Murdoch appears for a brief moment to bid farewell to Bigelow, and the strings and winds’ rising figure in a major key suggest that he will now at last rise to heaven; this is confirmed by the spirit-voice of his father. Swelling strings, harp, and bells (1:16:27) accompany Murdoch as he also says goodbye to his kinsman Donald, and Murdoch’s spirit fades away with the music’s cadence.

17. The Glourie ghost was a familiar kind of spirit to audiences conditioned to the concept of spirits made to wander—or who wanted to—until some final wish or task was complete. Murdoch Glourie, like many a spirit who spoke at séances, only wanted to fulfill the condition needed for him to move on to a different realm. Although he is at times threatening, and treated as such musically, these moments are scarce and dissipate quickly, becoming comedic or triumphant. For most of his appearances, Murdoch is just another lonely spirit passing time on earth while pining for heaven, and the audience is told just that through Spoliansky’s references to traditional signifiers: bells, shimmering percussion, chromatic lines in various instruments, and the harp.

18. Composer Marvin Hatley also drew on the sounds of the séance and the music for silent spirit films in scoring the 1937 film Topper. His employment of the same musical tropes and techniques that both Trytner and Spoliansky used testifies to the continued recognition of silent film accompaniments for spirits, as well as the ongoing practice of relying on musical meanings established in the silent cinema.

19. Directed by Norman Z. McLeod, Topper was described by film critic Mildred Martin as a new entry in the genre established in the silent era of “gentle ghosts, romantic ghosts, tragic and bewildered ghosts,” comparing its “gay ghosts” with the “irresistible phantom lady killer of The Ghost Goes West.” (Martin 1937) A wealthy, irrepressible, fun-loving couple, George and Marion Kerby (played by Cary Grant and Constance Bennett) die in a car accident and, finding their spirits still on earth, decide that to get to heaven, they must do a good deed. They decide to haunt their friend, the staid Cosmo Topper (Roland Young) and make his life happier and more carefree. Episodes of comedic misunderstanding follow until finally Topper and his wife relearn to have fun, and the Kerbys depart.

20. At the beginning of the film, Hatley establishes Hoagy Carmichael’s “Old Man Moon” as a primary musical theme of the score. Carmichael himself plays it once at the beginning of the film, and different dance bands play it in later iterations as the Kerbys go club-hopping. This provides metadiegetic musical continuity for Topper, with the source of the music coming from inside film’s doxastic world. While today we might read the song’s lyrics are problematic—the singer asks the moon to help him seduce a woman by dazzling her with its light and drugging her drink with “stardust”—at the time it was promoted as a fun and romantic song.

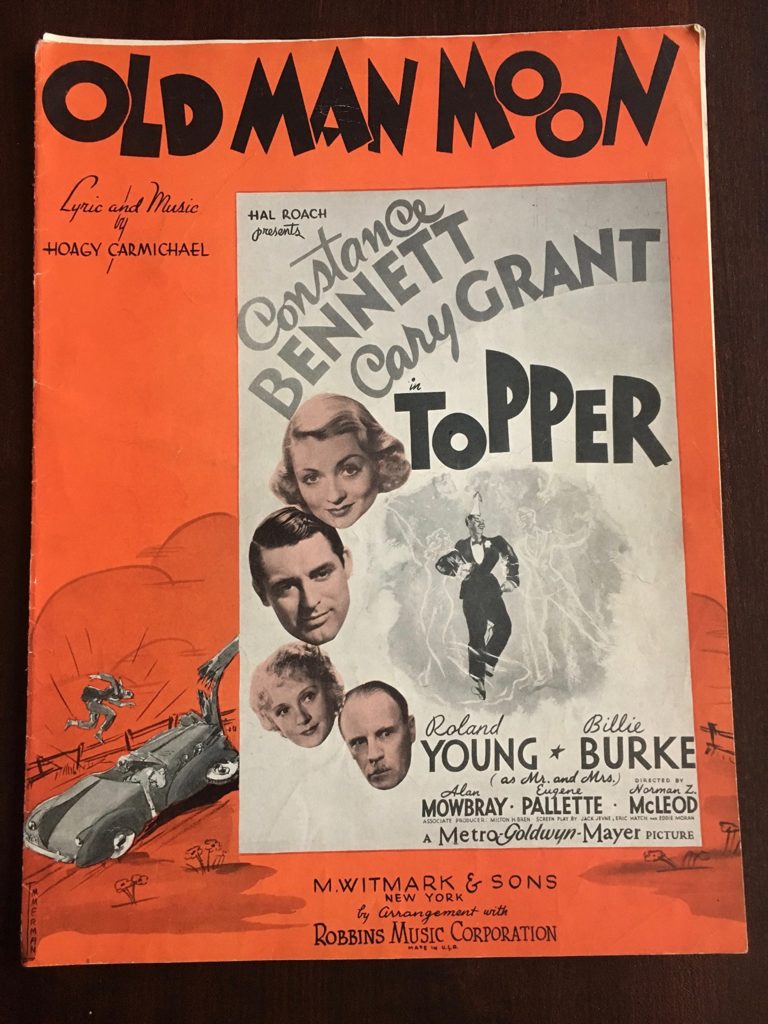

21. Carmichael’s mother was a silent film accompanist, and it is possible that he too played piano for the movies growing up in addition to playing for dances and at clubs both as a soloist or part of a small band. He began writing songs for films in 1936, composing “Moonburn” for Anything Goes and joined Paramount Pictures in 1937 as an in-house songwriter for the movies. Carmichael’s “Old Man Moon” is used much in the way that popular songs written for silent films were employed as themes and as marketing tools. The sheet music for the song shows the car accident that kills Marion and George, and their ghosts walking with Topper (Fig. 4.2). The focus on the names of the film’s stars and title threaten to overwhelm the song title, which is pushed to the very top of the cover page.

Fig. 4.2. “Old Man Moon”

22. Although “Old Man Moon” doesn’t address the spirit world, plenty of other music in Topper comes straight from the séance. The score and instrumental sound effects for Topper suggest that George and Marion Kerby will become ghosts well before their actual deaths: George plays notes on the rim of a glass while at the Rainbow Club, referencing the eerie sound of the glass harmonicas used in séances and on stage and in silent cinemas to indicate the presence of the unworldly. He sings and hums without seeming to notice what he’s doing, much like a medium demonstrating contact with or control by a spirit.

23. When the Kerbys do die, George waits to hear trumpets—another sound repeatedly associated with both séances and death—but none come. It is this lack of music that suggests to the Kerbys that perhaps they can’t ascend to heaven until they’ve done something worthwhile on earth. Their assumption of this condition only makes sense to audiences familiar with the concept, either through literature (like Hamlet, as cited above) or through Spiritualist beliefs and earlier spirit films like Earthbound. Sound and music continue to play a large part in both the diegesis and metadiegesis through the end of the film. The human-based sonic abilities of the ghosts, including singing of popular songs, children’s songs, and Marion’s whistles after Topper requests that she “make a noise every now and then so I know where I’m talking to,” imbue them with audible capabilities familiar from séances and keeps the ghosts (and the film) in the genre of mischievous and benevolent spirits and the spirit film.

24. Topper score composer Hatley worked in silent film prior to his employment as a composer for sound films, so it is not surprising that the score for Topper is constructed much like a compiled score for silent film in its use of generic, mimetic musical pieces. There is fast-tempo chase music for scenes of the Kerbys driving, and hurry music for Topper as he runs to catch a train. There is not always music for the ghosts—the first time they appear to Topper, there is only the sound of their voices to precede their becoming visible—but where there is underscoring for the ghosts, it is in the established mysterioso style, albeit sometimes in a major key. In the scene in which an invisible George and Marion escort Topper through the lobby of their building, Hatley uses pizzicato strings and short motifs alternating between the upper and lower winds to create an accompaniment that nods to both the classic mysterioso with its pizzicatos and descending lines and to comedic genre music that relies on contrasting registers and timbres.

25. When the police search for George at 1:30, the diegetic music of the ballroom—“Old Man Moon” again—falls silent and the score takes over. The score begins with a standard mysterioso in a minor key using low-pitched instruments and at a walking tempo with staccato chords that mimic the policemen’s movement. After about sixty seconds, however, the search for George becomes more madcap and the music changes to suit. While Hatley doesn’t make it as comedic as the scene in which Topper stumbles through the lobby, he does change it to indicate the presence of the fantastic through trills and glissandi. The texture lightens so that instead of low-tessitura winds and brass, the violins and flutes now have the primary motifs of trills followed by brief descending and ascending lines. By the time Topper’s driverless car pulls up for the main characters’ escape, the pace of the music has quickened and the glissandi—now with harp—are clearly intended to signify the magical, as interpreted through the stage and silent cinema. Shortly thereafter, following a brief scene of wild driving with chase music, Topper’s car crashes, knocking him unconscious. As his spirit rises away from his body (1:32), he is accompanied by a rising and falling motif in the bassoon that suggests his liminal state. When the Kerbys notice his spirit, a stinger chord in the brass followed a descending third in the oboe mimics their surprise. As Topper expresses his desire not to go back to his life, Hatley gives the bassoon a longer descending line, suggesting Topper’s desire to be dead.

26. However, Topper’s spirit returns to his body and wakes up at home, where he finds that his unpleasant, disapproving, and stodgy wife has changed into a far more supportive and loving companion. A rising string figure accompanies Marion’s and George’s faces as they dangle form Topper’s roof to bid him farewell through the window, indicating that their “good deed” in enlivening Topper’s life has been accepted by heaven and that the Kerbys will now be admitted.

27. There are also a number of visual references to mediumistic tricks in Topper as well: George writing his name upside down and backwards at his bank meeting and slithering in and out of his seat are both nods to the abilities of spirit mediums (beginning at 14:45). Once dead, both ghosts manipulate physical items while unseen, mimicking the floating items seen at séances, and in the scene beginning at 33:06, George tells Marion he “won’t waste ectoplasm” to be visible while changing a car tire. Later in the scene, two passers-by are frightened away by the sight of floating car tires and the sound of Marion’s voice and whistling; later, a man is taken aback to see Topper’s car apparently being driven by no one. Taken all together, Topper offers a catalogue of séance activities transposed to the sound film.

Legacies of the Silent Spirit Film

28. The spirit is a disruptive force, regardless of its intent, and spirits demanded music and sound that was equally disruptive of normate music for accompanying non-supernatural moving images. As cinema musicians developed a soundscape for haunting, they were themselves creating a haunting (as defined by Carlson) of the cinema by the sounds and music borrowed or replicated from the séance and the opera, which were themselves haunted by sounds created in the natural world that spoke to audience desires to hear the unnatural. (Carlson 2003) Mediums and musicians listened closely to each other for musical means that would compel audiences to hear what they thought being haunted sounded like. The resulting body of tropes, gestures, and textures has been used whole-cloth and in select bits to the present. Although some musical tropes from spirit films have been co-opted by horror media and others by gothic works—the sounds of a music box, organ, or music played autonomously by other devices, for example, for all of the supernatural, not just spirits—much of the music composed more recently for spirit films is similar to that of the 1910s and 1920s.

29. Edith Lang and George West’s recommendations, the borrowing of music and sound from séances, genre music for the mysterious and unworldly, hymns and songs sung by Spiritualists, and musical signifiers associated with various kinds of afterlives have been resilient in film scoring. The ghost-comedy genre, which developed from films like The Ghost Goes West and Topper, and films about gentle or needy ghosts have continued through the twentieth century into the twenty-first, where audiences can still hear organs, bells, celestas, self-playing radios, and other devices, all descended from silent cinema. The trope of the haunted organ—which overlaps with both the haunted instruments and the haunted technologies of the séance—has become a cultural icon for hauntings, most often of the benevolent-ghost type, and sometimes of the not-ghost-but-presumed-to-be-a-ghost type, seen in numerous film versions of The Phantom of the Opera and in Scooby-Doo. As Isabella van Elferen has noted, the organ as a whole has become closely associated with spirits of both the benevolent and malevolent kind: “Organs, in cinema or in other contexts, always stir associations not only of sacred music, but also of their traditional location in churches and cathedrals, near crypts and graveyards.” (Elferen 2012, 38) Even modern horror scores use select sonic tropes from silent spirit films, often in explaining the origin of a spirit. Modern spirit films, generally featuring traditional ghosts with unfinished missions, are accompanied by scores that offer bells, instruments or musical technologies played by unseen forces, mimesis for the appearances, disappearances, and actions of ghosts, religious music, romantic songs or numbers, shimmering percussion, tremolo, sul ponticello, and gentle stingers that are intended to point out a scene and the information it transmits rather than create a jump scare.

30 . The 1947 spirit film The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, in which the ghost of a sea captain and a young widow fall in love, is scored by Bernard Hermann, who would have attended silent films as a child and frequented the opera in his youth. Hermann uses multiple techniques for accompanying spirits from silent film practices in his orchestral score for this spirit film-romance. Violins playing high in their ranges, shimmering cymbals, and the occasional dissonant chord suggest early on that there is something mysterious and likely supernatural about Gull Cottage, the house Mrs. Muir rents that is home to Captain Gregg’s ghost. A light stinger accompanies Mrs. Muir as she opens a door to see the painting of Gregg for the first time, foreshadowing his later arrival as a spirit. For the most part, Hermann’s dissonances, tremolos, and chromatic lines resolve into brief sections of major key ordinariness, telling the audience that the spirit, when he arrives, will be like the Glourie ghost or the Kerbys: entirely human in appearance, a bit mischievous, and decidedly non-gory. In fact, the ghost (despite his astonishing chauvinism) is attractive enough that Mrs. Muir falls in love with him and happily joins him in the afterlife on the day she dies.

31. Following a storm outside, which is accompanied by generic storm music that could have come straight from a photoplay album, Mrs. Muir addresses the ghost, whose presence she feels in the cottage. (18:00) The music that accompanies her request for the ghost to speak is limited to upper winds and strings, and while a little eerie is not indicative of horror but of a roguish spirit. Captain Gregg’s first lines—heard while he, like Jacob Marley’s ghost in the 1935 Scrooge, is off camera—are accompanied by contrasting low winds. As the Captain and Mrs. Muir speak for the first time, the score disappears only to come back near the end of the scene. The same forces are in use, but the eerie sustained flutes and violins have shifted into a more active line that is pastoral in nature. Soon the clarinets and lower strings have taken over as the dominant instruments, and the audience is to understand that the agreement between the two characters will lead to a pleasant relationship. At the end of the film, when Mrs. Muir joins the Captain in death, she is accompanied by sweeping strings and harp, followed by a dramatic rising figure in the brass that ends with trumpet fanfares signifying their transition to heaven as the two walk away together from the cottage.

32. The Ghost and Mrs. Muir is just one of many such spirit films made well after the advent of sound that rely heavily on the musical and aural signifiers developed by silent cinema musicians to accompany spirits. Such films include the 1966 The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, which uses the haunted organ; spirit/horror-comedy Trick or Treat (1986), in which the spirit of a rock star controls a record player and other instruments; Ghost (1990), in which a spirit possesses technology and rises to heaving to rising string and wind lines coming out of the film’s main theme, pizzicato simulating a harp, and, finally, rising harp arpeggios; 1998’s Beetlejuice, in which the ghosts realize they are dead to the sound of several stingers of which Edith Lang would surely have approved (Halfyard, 2010, 23).

33. In The Muppet Christmas Carol from 1992, the score employs traditional spirit music for Jacob and the created-for-film Robert Marley (played by Muppets Statler and Waldorf), including oscillating pitches at the door-knocker scene and the use of with whistles and xylophones as “bones” for the appearance of the Marleys’ ghosts. String trills and tremolos, rising harp figures, shimmering cymbals, high-register violins, winds, and percussion, and automated music from a clock signify the arrival of the Ghost of Christmas Past. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come enters with high strings, shimmering cymbals, and low brass, strings, and rolls on the tympani and bass drum. Pizzicato in the mysterioso tradition accompanies Scrooge as the Ghost leads him through time. When Scrooge visits his own grave, the scene begins accompanied by high, sustained strings and a wandering, chromatic line in the winds that is a variation on the film’s primary theme, along with bells and distant horns. As Scrooge realizes that his life “can be made right,” the strings are given a rising figure, followed by a trilling, ascending line throughout the entire orchestra with emphasis on the sleigh bells and harp. According to the score, Scrooge’s spirit—still inside of his body—is nonetheless now destined for heaven.

34. More recent films also demonstrate the continued use of musical tropes from the silent spirit film as well: Stardust (2007); 2009’s Coraline; the 2016 Ghostbusters; the Harry Potter films; numerous Scooby-Doo movies; and other cinematic dramas, comedies, and fantasy productions featuring the supernatural all have scores that include the sounds of the séance and silent spirits. Even as of this writing, in late 2019, séance attendees (and ghost hunters, who seek out the paranormal through the use of light- and sound-sensing equipment) expect a soundscape of rappings, instrumental music played by unseen hands, interference with sound-(re)producing and other technologies, and additional forms of unexplained or sudden music or other sound.

35. That the sounds of spirits created by mid-nineteenth century mediums and later expanded upon and reified by both mediums and cinema musicians are so persistent suggests several things about these sounds and their transmission. To begin with, it is clear that mediums and early film accompanists had tapped into a cultural zeitgeist, as it were, in which the sounds they developed for spirits clearly met audience expectations or reified previous audience experiences. Particularly for cinema audiences in the early part of the twentieth century, the use of audience-anticipated sound, judged to be appropriate for the images being shown, was essential for not only communicating a film’s intent, but also for providing verisimilitude for the situations shown. An audience wouldn’t believe the scene or the music if the two aspects of the film didn’t match what the audience expected. This is why playing inappropriate music that “gigged” or “kidded” a film was so often decried in film music criticism of the silent era—it went against all audience expectations and was disrespectful of the apparent intentions of the film. As the séance was the most widely known source for the sounds of spirits, film accompaniment for spirit films had to have been convincing to audiences familiar with the conventions of séances. As film accompaniment became more specialized and sophisticated, spirit music also developed into its own genre, overlapping in some cases with mysteriosos, hurries, and suspenseful pieces. That specific kinds of music for spirits were regularly (re-)published and recommended indicates the genre’s success in fulfilling the anticipations of audiences of both séances and spirit films.

36. The longevity of this repertoire and pieces written to join it is significant as well. As I’ve demonstrated, a substantial number of musical signifiers that developed out of the séance and silent cinema are still very much in use. This suggests that early cinema musicians created accompaniments that were not only apposite representations of the séance, but that their accompaniments for spirits resonated strongly enough with early cinematic audiences to cement the connection between specific musical material and the supernatural on screen. That sound composers continued to use the same materials indicates that this connection was deeply embedded in public consciousness and that to replace it or alter it significantly was unnecessary if not unwise. Many composers for the early years of sound film grew up attending silent cinemas where cinema musicians constantly reified the musical conventions for numerous genres, including the spirit film.

37. The history of women as film music tastemakers in spirit films has also continued to the present day. Scores by women, drawing on traditional music and sounds for spirits and incorporating more recent signifiers of ghostly presences—such as electronic sound and music—have led and influenced the ongoing development of the sound of spirit films (as well as horror). Daphne Oram’s electronic soundscape for The Innocents (a 1961 adaptation of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw) uses musique concrète—found, recorded sounds—along with the manipulation of electronically-created sounds to create an atmosphere redolent of the séance and early spirit film. Oram used the sound of a music box, the sound of wind, continuously oscillating sine waves—similar to the oscillations often used in the strings in generic music for the silent spirit film—that are ended with glissandi, and fragmented, musical laughter from unidentifiable sources. And although their scores were for movies generally regarded as closer to horror than spirit films, Delia Derbyshire, Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind (The Shining, 1980), Elisabeth Lutyens, and Shirley Walker (Final Destination, 1990) all composed music for ghosts that use and continue the tropes that originated in silent spirit films.

38. Although Spiritualism has receded from public view, its practices and their depictions in silent film music remain an integral part of how composers and audiences understand spirit presence and communication in movies. Few filmgoers today will have attended a séance, but most will be familiar with the sounds of spirits in attendance: it is a soundscape that persists, resists, and endures.

Sources

American Organist Vol. 12. 1929. American Guild of Organists (New York).

Carlson, Marvin A. 2003. The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

David, George. 1935. “‘Scrooge’ Fine English Cinema On New Regent Program.” Rochester (NY) Democrat and Chronicle, December 19, 1935.

Edison Phonography Monthly. 1911. “Foreign Records for December, 1911,” December 1911.

Elferen, Isabella Van van. 2012. Gothic Music: The Sounds of the Uncanny. Gothic Literary Studies. Cardiff: Univ. of Wales Press.

Exhibitors Herald. 1924. “The Theatre,” January 12, 1924.

Halfyard, Janet K. 2010. “Mischief Afoot: Supernatural Horror-Comedies and the Diabolus in Musica.” In Music in the Horror Film: Listening to Fear, 21–37. New York: Routledge.

Hazelgrove, Jenny. 2000. Spiritualism and British Society Between the Wars. Manchester University Press.

Leonard, Kendra Preston. 2018. “Musical Mimesis in Orphans of the Storm.” Music Theory Online 24 (2). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.18.24.2/mto.18.24.2.leonard.html.

Martin, Mildred. 1937. “These Film Phantoms Are All in Good Fun.” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 1, 1937.

Moving Picture World. 1917. “Miscellaneous Subjects–Bluebird Photoplays Inc., The Right to Be Happy,” January 6, 1917.

Pittsburgh Press. 1929. “Canned Music on Trial (Advertisement),” 1929. https://repository.duke.edu/dc/adaccess/R0206.

Shakespeare, William. 2006. Hamlet. Edited by Neil Taylor and Ann Thompson. Third Series. Arden Shakespeare.